In her new book, Associate Professor Trica Keaton shows how France perpetuates antiblackness in daily life even as it promotes an ideology of blindness to race.

Trica Keaton traces her interest in pursuing academic research to a clear goal: "crushing racism and injustice wherever I can in the world."

Growing up in a small town in Ohio, Keaton found "few opportunities for Black and poor kids, irrespective of heritage," she says. "I simply wanted to find a world where I and others would not be judged or harmed by race and racism."

Ultimately, Keaton decided to become a professor for "the capacity to empower others through what we research, teach, and write."

An associate professor affiliated with the departments of African and African American Studies, Sociology, and Film and Media Studies, Keaton researches the lived experiences of racism in the United States, Western Europe, and especially France, where she pursued graduate studies in sociology in Paris at L'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and L'Université Paris V. She is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center Fellowship, Columbia University's Institute for Scholars Fellowship at Reid Hall in Paris, and the Chateaubriand Fellowship.

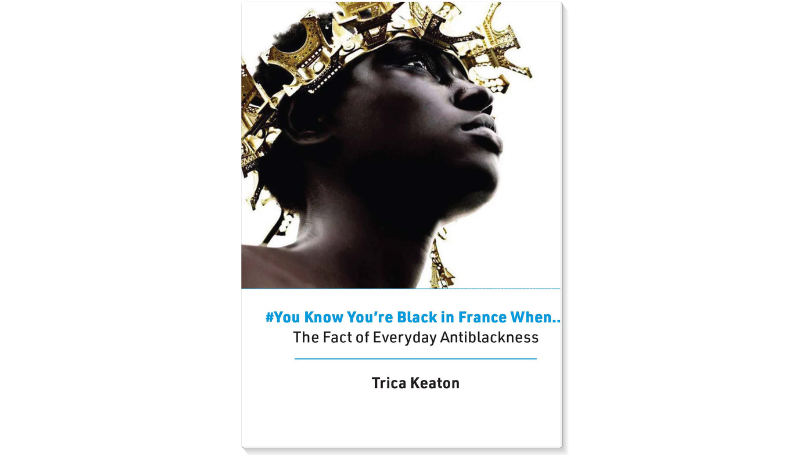

In her new and fourth book, #You Know You're Black in Paris When: The Fact of Everyday Antiblackness, Keaton explores how France perpetuates antiblackness—"a dehumanizing racialization in terms of black inferiority"—even as it promotes an ideology of blindness to race. The book was selected as a "Choice Pick" by the Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association.

In a Q&A, Keaton reflects on her interdisciplinary study of race in France, the impetus for her new book, and its implications for other countries.

You've described your work as interdisciplinary social science. How does your research push traditional boundaries?

Although I was trained as a social scientist, my work transgresses established disciplinary boundaries. While sociology is fundamental to how I conceptualize and think critically about the lived experience and issues that I explore in my work, African Diaspora studies and film studies allow me to dance with the arts, visual culture, and the humanities more broadly. I can cast a wider net when exploring issues ranging from how power is represented and accessed to police violence to analyses of films and art objects.

My next book examines racialized representations in French cinema, and I'm developing an institute and digital humanities project on the study of Black life in France, which will also provide research and publishing opportunities for students.

What was the impetus for this book?

This book was a long time in the making, but worth the wait. It really is the culmination of years of living in France, and more specifically in Paris, as an undergraduate, graduate, postdoc, and visiting scholar. I witnessed and experienced, on far too many occasions, recurring aggressions and violence—which are ultimately the same thing—when doing or seeing others carry out normal everyday tasks.

It was not because of anything we had done, but because we had been racialized in certain ways in a society that is itself racialized. A classic example is being asked the proverbial question, "Where are you from?" with the "from" referring to one's parents' countries of origin. This is not innocent. For nonwhite people, this query calls their belonging and citizenship into question. Ridicule, racial profiling, and often unspoken brutality are among other examples that I document in my book.

The French state tells a story that France is one people and one nation, where equality resides in "disappearing" racial differences: equality through invisibility. Or, as a participant in my study told me: "I don't exist in France. As a Black French woman, I do not exist." But everyday life is anything but blind to race.

What does it mean to be "racialized-as-Black" in France on a daily basis?

I'm using racialized-as-black conceptually for understanding the lived experience of black race-making, so I'm emphasizing a process by which people of African descent are apprehended and categorized in terms of racial inferiority or a less-than status, and are thereby identified with social problems such as crime, educational failure, unwanted immigration, blighted neighborhoods, and more. At the same time, young people especially have been scripted as problems that must be managed and controlled by so-called "problem solvers," largely the police or law enforcers. In other words, it's about how race-thinking operates, and to what end.

One participant expressed it when describing the multiple times that he has been stopped by the police: "There's a dynamic, for me as a French person, that I experience: a feeling of being a second-class citizen. And it seems that no one recognizes that I have a certain dignity, or what it means to be subjected constantly to these controls as a citizen."

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

The main takeaway of this book aligns with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s lucid insight: "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere."

Another takeaway is that b/Black (racialized and politicized) people are a distinctive group in a race-blind context, in that their racialized blackness explicitly connotes race in ways that set them apart from other racialized groups. At the same time, they are unprotected "national minorities," actually minoritized people, in a France that does not accord them a legal "minority" status; thus, they lack protections and rights, making it extremely difficult to find political and legal redress to violations of their rights. You cannot effectively battle a problem that you are not allowed to see.

As extreme "anti-othering" discourse reclaims the mainstream and has become the "next normal" for a new generation, I hope that reading this book will provide some insight into the deleterious reality of antiblackness and how damaging it is across generations, particularly for those not on its receiving end.

Did you learn anything particularly surprising when researching this book?

I was somewhat surprised, but also inspired, by the cases in which people are fighting back and winning against the French government! What these cases show is that, despite entrenched beliefs and evidence to the contrary, the French state can be held accountable when its police force violates those rights.

At the same time, it's telling when advocates of French race-blindness instrumentalize African American expatriate lore to score political points and finger-wag at antiracism activists and others in France battling these issues—in other words, asserting that if things were so bad here, why would African Americans expatriate or immigrate to Paris?

I'm reminded of an exchange between a French ambassador and a journalist during the summer of reckoning that followed George Floyd's murder. The journalist tweeted: "As #BlackLivesMatter reverberates around the world, can France still credibly refuse to recognize race?" The politician's response is classic French race-blindness and misdirection: "No," responds the ambassador, "France won't' 'recognize race.' Don't project on us an American model. Our history and our historical fabric are different. We'll have to face racism but in our own way. A lot of African Americans don't think we are that bad."

Does this research have implications for the U.S. and other countries, too?

Yes, indeed. As I show in my book, drawing on studies and reports from the European Union and parliament, several continental European countries subscribe to race-blind principles that erase race problems and attribute them to other so-called societal woes. Immigration, Islam, and insurmountable cultural differences become the proxies to explain away those "problems."

I also highlight several parallel cases involving police violence in France and the United States. The differences, as I argue, are not of kind but degree. The murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter movements resonated strongly in France precisely because these issues are all too familiar.